Dear Company: You are using me all wrong. Sincerely, your chief financial officer.

That is the message coming in loud and clear from more than 60 bank CFOs contacted by American Banker through a survey, questionnaire or interviews in recent weeks.

Nobody knows their banks' numbers better than the CFOs do, and they want to weigh in on strategic matters such as how to rev up revenue growth or how to respond to the competitive threat from fintech companies. Unfortunately, many financial officers are spending more time than ever handling compliance, data-collection and other routine tasks rather than thinking big.

-

Institutional and private-equity investors are more demanding of regular face time with decision makers like CFOs, who better be prepared to answer questions not just about balance sheets and income statements, but also underwriting standards, loan concentrations and accounting methods.

May 31 -

Trade groups for both industries put aside differences to seek congressional signatures on a letter urging FASB to reconsider its controversial proposal requiring early-stage loan-loss provisioning.

February 2 -

LAS VEGAS Office of the Comptroller of the Currency chief Thomas Curry said Thursday that banks have reached a do-or-die moment and it is up to them to keep up and outinnovate nonbank rivals.

April 7 -

That is the message from North Carolina's banking commissioner and others who think the odds of preventing the rule are so low, and the amount of preparation needed to comply so great, that bankers should get real.

March 10 -

If banking is under attack, then chief financial officers are the defenders of the realm. Equipped with the numbers, they are uniquely positioned to bring the credible answers their stakeholders seek and the changes their companies need.

May 3 -

A chief financial officer's workday is booked solid dealing with regulatory issues, risk assessments and finding places to cut costs. If they could find an extra hour, bank CFOs say they would use that time to consider how to improve their banks' strategies, employees and communities.

May 3

"We end up focusing on things that are defensive in nature that aren't additive to our business model," said Larry Sorensen, CFO of the $5.3 billion-asset Washington Trust Bank in Spokane. "There isn't enough time to give [important strategic] things their due. … We as an industry will end up paying for it."

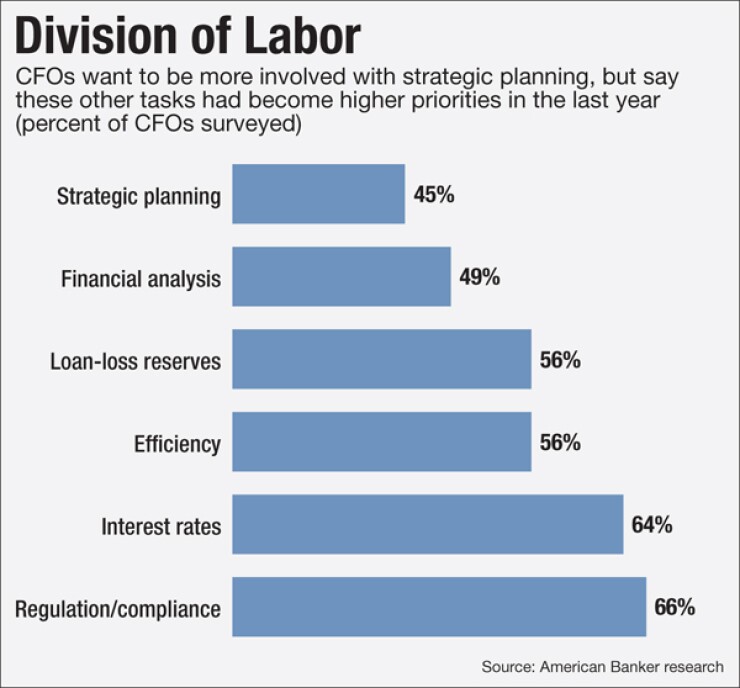

Granted, 45% of the CFOs surveyed said that they have played a greater role as strategic advisers over the last 12 months. That seems like a big number, except when compared with feedback about time spent on more mundane matters.

Two-thirds of the CFOs said compliance and the basics of interest rate risk management had become a higher priority in the past year. And more than half said that the managing loan-loss allowances, including preparation for

"I find that most of our leaders, including me, are pigeonholed into particular roles that restrict our ability to influence the entire organization," said Daryl Drewett, the CFO of the $795 million-asset First Federal Bank of Louisiana in Lake Charles. "Many of us could be more useful to the bank if we were able to act in a more collaborative capacity, sharing our ideas on how to move the bank toward its strategic goals."

Such frustration makes sense in light of how typical CFOs spend their day, said Marty Mosby, director of bank and equity strategies at Vining Sparks.

"If you look at the tilt, it has been skewed very heavily toward regulatory tasks rather than tactical," added Mosby, who was the CFO of First Horizon National in Memphis, Tenn., from 2003 to 2007. "Strategic planning gets whatever time is left."

It is an old problem for CFOs that's getting worse, said Aneel Delawalla, managing director at Accenture Strategy. "What is new is the velocity of change and the scope of disruption that is distracting CFOs," he said.

Challenges, Distractions

Fintech, in particular, presents a challenge that bankers must address. That issue gained added prominence recently when Comptroller of the Currency Thomas Curry told attendees at

CFOs say they are eager to take a more active role in, say, the long-term planning about how banks will upgrade deposit and lending systems so they can compete with speedier, consumer-friendlier online lenders and neobanks.

Yet if you ask CFOs where they are spending the bulk of their time, the vast majority will point to compliance, including call reports, stress testing, mortgage rules and, for larger institutions, the liquidity coverage requirement.

"Compliance and stress testing demand more of my time now than they have in the past," said Clint Stein, CFO of Columbia Banking System. The $8.9 billion-asset company has spent the last three years preparing to cross $10 billion in assets, where it will face mandatory stress testing and caps on interchange fees, he said.

Haynes Standard, CFO at First State Bank in Wrens, Ga., noted that the regulatory environment has also contributed to a spike in the number of reports he has to prepare for his $103 million-asset bank's board. "Financial reporting takes up most of my time," he said. "This includes call reports as well as internal board reports."

Several CFOs noted that they are trying to prepare for the accounting standards board's proposed Current Expected Credit Loss model for loan-loss reserves. Industry experts have been urging bankers to

Preparation for CECL "is just starting in earnest," said Jason Hicks, CFO of the $1.5 billion-asset New Hampshire Mutual Bancorp in Concord. "That is certainly the newest development that is garnering more attention."

A number of CFOs also pointed to cost-cutting — a typical, short-term industry response to sluggish revenue growth and higher regulatory burden — as an area where they are spending a significant amount of time.

John Michel, the CFO at the $2.6 billion-asset First Foundation in Irvine, Calif., said he spends "more time on evaluating interest rate risks and monitoring efficiency as compared to a year or two ago."

Staffing cuts themselves are another reason financial officers are unable to devote as much time as they would like to the future. Employment at commercial banks is down 7% since mid-2008, falling to less than 1.3 million in March, based on preliminary data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A number of CFOs said they have been forced to take on added responsibilities as a result of budgeting issues.

"Given the opportunity, I'd like to focus more on strategic planning, but I now wear more hats and have taken on more roles due to margin compression and budgets not allowing for additional staff," said Kimberly Kling, the CFO of Morganton Savings Bank in Morganton, N.C.

Careful What You Wish For

All that said about the relative isolation of CFOs from key decision-making, they can get caught in the crossfire when banks have problems.

The embattled Comerica said May 3 that its CFO of the last five years, Karen Parkhill, was out, replaced by the general auditor, David Duprey. The move raised questions about whether she had been forced out because the $71 billion-asset Dallas company's exposure to the energy crisis, lagging returns in recent years and rough first quarter had landed it in the crosshairs of activist investors.

But a day later the medical device maker Medtronic said that it had hired Parkhill as its CFO because of her range of experience and service on a health system board, and that it welcomed the "ideas and perspectives" she would bring to management in a time of industry change.

Parkhill, in an interview in March for this story, echoed the sentiments of many bank CFOs about the nature of their jobs. The impact of the Dodd-Frank Act was visible every day, she said. "Since assuming the CFO role in 2011, I have focused on stress testing and capital planning, especially, among other areas resulting from the new regulations," she said.

And cost-cutting was an overriding priority. "Maintaining our expense discipline is vitally important" because of the low-rate environment, Parkhill said in the interview.

Comerica's announcement implied perhaps a wider role for her successor, Duprey, as the company conducts a strategic review with the help of an outside consulting firm.

He "will play an important role in driving the future of Comerica and creating value for our shareholders — especially in working with Boston Consulting Group in its current review of our revenue and expense base," Chairman and Chief Executive Ralph Babb said in the news release that announced Duprey's promotion.

Possible Solutions

If more CFOs are going to take increasingly prominent roles at their companies, they will have to take steps to re-engineer their jobs.

There are ways for financial officers to free up time without spending a ton of money, industry experts said. Banks should consider bringing in interns to collect CECL-related data required by the accounting standaards board, said Walter McNairy, a lawyer at Dixon Hughes Goodman in Raleigh, N.C.

If possible, CFOs should find ways to delegate some tasks, the analyst Mosby said. "It helps to have strong leaders underneath you in those areas such as risk management and accounting, so you don't have to shepherd all those initiatives," he said.

Bankers should also consider creating support groups to discuss ways to reduce workload to allow for more strategic planning, Mosby said. Sorensen at Washington Trust agreed, noting that there is a need for more CFO roundtables to discuss topics such as time management.

Increased use of technology — including big data, robotics and cloud computing — could also make "the basics of a CFO's job simpler so they can pivot," the consultant Delawalla said. "CFOs know they need to keep an active posture and make changes … and the same tech that is disrupting them can also become an enabler," he said.

Of course that is easier said than done at smaller institutions with limited budgets. "There is a distinction between the size of a company and its ability to invest and its range of options," Delawalla conceded.

However, some CFOs said they have been able to make strategic planning a priority and advised their colleagues to be more assertive.

"Today's CFO must have a keen understanding of the client base, as well as the markets the bank serves, in order to develop initiatives and recommend strategies that will further the bank's financial goals," said Edward Czajka, the CFO of the $2.6 billion-asset Preferred Bank in Los Angeles.

While it is a "great challenge" finding time to plan for the future, "we have a great team of strategic thinkers leading our company, so it is ingrained in our DNA as we approach our daily work," Czajka added. "We meet formally on a weekly basis, and daily on an informal basis, and there always seems to be discussion not only on current pressing matters but also on strategic initiatives."

The solution is in the hands of the CFOs themselves, and banks will be better off if they are successful in being heard, Czajka and others said.

"CFOs are trying to shift their mindset … to levels of profitability and opportunities to grow organically and through acquisitions," Mosby said. "They need to find a way to productively use capital in the very best way over the next three years. That's the shift that has to happen."